What Would You Do With Eleven Trillion Dollars?

Introduction

Back in March 2024, I interviewed Ian Edwards and Tim MacDonald at Bank of Nature for my piece, Investing in Forever. Ian and Tim made the case that defined-benefits pension plans could do more than any other institution to help steer the economy and society away from social and ecological collapse toward a harmonious, prosperous future for all. Yet pension administrators, fixated as they are on maximizing returns from the stock market, have no idea this is possible.

The interview opened my eyes to what pension administrators are not doing, and what they could—or should—be doing. As Ian and Tim explained, a pension fund is a forever machine, designed to provide returns to its members into perpetuity. In the old days, pensions would accomplish this through safe, long-term investments, such as government bonds. But over the past fifty years, pension administrators have become speculators in the stock markets, in pursuit of better short-term returns.

The problem with this approach is that the same short-termism of the market sets up a misalignment with the long-term strategy of pensions. Financial market transactions are in-and-out transactions. Stocks, unlike government bonds, typically are not held for many years. Pension administrators thus become subject to what evolutionary biologists call the Red Queen effect—running to stand still[1]—by having to constantly trade in the markets to meet a pension’s target rate of return. Because pension plans move vast sums of money around, their trading inflates prices in the stock market, which in turn inflates the values of assets in the real economy, eventually creating a credit bubble, which always bursts.

Furthermore, as Ian and Tim argue, trading in the stock market violates the fiduciary promise of pension administrators to provide good stewardship over their members’ money. The market, being near-sighted, is blind to the planetary footprints of the companies whose stocks are traded on it. If pensions are on the hook to provide for the future then why are they investing in companies, such as oil and gas, that are liquidating that future? Ian and Tim argue that pensions should be leveraging their assets to improve the future, not diminish it. Anything else is a violation of their fiduciary duty, for which they could be sued.

The scale of the pension effect upon the financial markets is revealed by data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Worldwide, pensions of all kinds hold around US$56 trillion—yes, trillion—in assets, almost all of which is invested in the financial markets. Among the 74 countries surveyed by the OECD, the lion’s share of that—$39 trillion—resides in American pension funds. This amount alone is 40 percent more than the United States’ gross domestic product (GDP).[2] Worldwide, the value of pensions is 66% of the total GDP of the countries surveyed—around $89 trillion—an amount very close to the world’s gross global product.

Put another way, $56 trillion for our collective future is sloshing around in public markets solely for the purpose of making short-term profits.

If that $56 trillion were pulled out of the financial markets, the effects on the markets, and the rest of the economy, would be dramatic. The markets would contract significantly. The relentless boom-and-bust cycles of recent decades would give way to a state of relative calm in the markets. The real economy would benefit by being less financialized. People would be able to afford starter homes again. Granted, a whole class of superannuated financiers would find themselves seeking other employment; yet it is doubtful that the masses working two or more minimum-wage jobs to make ends meet would shed a tear for them.

Where could all that pension money go to make the world a better place? Ian and Tim propose that it should go into forever investments: long-term ventures delivering a predictable rate of return and enhancing both society and nature.

The argument was so compelling that I had to find out how it would work. In the interview, Tim outlined the mechanism by which pension money would invest in, say, a grid-scale solar array or an offshore wind farm, as examples of long-term investments in planetary enhancement. But he also tantalizingly dangled the possibility that pensions could literally buy out the world’s largest oil and gas companies, take them private, and steer them toward planetary stewardship.

Clearly, they have the money to do this. Out of the $39 trillion in US pension assets, roughly $11.5 trillion is held in defined-benefits pension plans—these being the ‘traditional’ variety of pensions promising a guaranteed monthly amount upon retirement, while the remaining $27.4 trillion is held in defined-contribution pension plans, exemplified by individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and employer 401(k)s. IRAs and other kinds of personal pension plans account for $16.9 trillion of this, with employer-matched savings making up the remaining $10.5 trillion.[3]

Defined-benefits plans used to be commonplace across all sectors of the economy until the 1970s, when private-sector employers began replacing them with defined-contribution plans. This shift coincided with the financialization of the economy as a whole and the redirection of pension investments from government bonds into corporate stocks. Defined-benefits plans today are confined largely to the public sector.

Although a mechanism exists for individual retirement account holders to invest in forever ventures, which we discuss below, the first objective is to align the $11.5 trillion in defined-benefits pension money with pensions’ fiduciary obligation to the long-term future. Where defined-benefits pensions lead, IRAs and 401(k)s, not wanting to be left out of the long-term gains, will likely follow.

Let’s buy ExxonMobil!

One-twentieth of the $11.5 trillion in defined-benefits pensions in the US would buy ExxonMobil. Let’s say a consortium of pensions ganged together to take ExxonMobil off the stock market. They would acquire all roughly 4 billion outstanding shares, at a current price of about $100 per share, for just over $400 billion. They would then de-list ExxonMobil from the world’s major stock markets, taking on its outstanding debt and other liabilities, which total an additional $164 billion.[4] Throw in $10 billion of operating capital to cover the transition, and you’ve got yourself one of the world’s largest oil and gas companies for a cool $582 billion.

Now what?

To find out, I had to delve into the depths of Tim’s financial model, and into his brain. The model itself is neither unusual nor novel. As Tim described, it is standard fare in commercial real estate, and has also been adapted for renewable energy projects. What is novel is the application of the model. Capital is put up to build a wind farm or acquire a property or a company. The steady revenue provided by the asset then pays back the capital investment over time. And time, in these deals, is on one’s side. As long as the asset continues providing reliable revenue, a pension plan (or consortium of plans) is in no hurry to be made whole. Pensions are not going anywhere, and neither is the asset. So here we have a temporal alignment of the interests of the investor and the enterprise.

In essence, it’s that simple, but there are some nuances to appreciate. First, a pension plan will typically seek an internal rate of return (IRR) around six percent. So, to be ‘made whole’, the pension must earn back the initial capital investment and interest on the investment until the project’s internal rate of return reaches 6 percent. This is actually a lot more than merely 6 percent on the capital investment because, until that investment is paid back, the pensions in a consortium continue to incur an opportunity cost of not being able to invest their money elsewhere. This ‘cost of money’ is six percent on the capital amount each year until the project’s IRR reaches 6 percent.[5]

The second nuance is that the enterprise itself will need operating funds. Not all of its net income can be used to pay back the equity. Some income must be returned to the company so that it can continue to do business. The ‘equity split’ between payback and operations extends the time to reach breakeven.

The third nuance is the presence of a third player in the system, in addition to the consortium of pension plans and the acquired company. This player is a ‘stewardship equity platform’ (SEP). Ian and Tim’s Bank of Nature is an example, presumably not the only one, assuming the idea took off. In a stewardship deal, the SEP takes the place of an asset manager in a brokerage deal. It manages the acquisition on behalf of the pension consortium and guides the acquired company’s operations toward planetary stewardship.

Pension investments: current practice

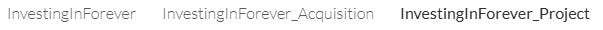

Today, when a pension plan invests in the stock market, it does so through an asset manager. The asset manager essentially relieves the pension plan of insourcing the required investment expertise. To see how the system works, we mapped it using Maporium’s system mapping tool. Click here to launch the map.

A defined-benefits pension plan takes contributions from employees and makes payouts to retirees. The contributions are placed into a pension trust, from which payouts are made. Withdrawals from the trust are invested by a pension plan’s investment office through a capital allocation to an institutional asset manager. Withdrawals also cover the asset manager’s fees. The asset manager makes trades in the stock and bond markets, earning returns that make their way back to the pension trust.

By way of context, the map adds a few other players in the system.

1. Distinct from institutional asset managers, retail asset managers invest on behalf of retail clients, such as private individuals.

2. Typically, a pension’s investment office is governed by a fiduciary board that may be advised by one or more pension consultants.

3. Increasingly, pensions are also guided by environmental, social and governance criteria, these being concerns for their members. Pension administration might include an ESG or sustainability office, which makes recommendations to the investment office.

4. Pensions are regulated in a variety of ways by the government, through fiduciary statutes, case law and operational compliance.

While a pension plan sees only returns on its capital allocation, what happens downstream from a market trade is important for understanding a stewardship equity model. Under current practice, an asset manager buying into the securities markets will interact with a market maker offering either debt security through the bond market or equity security through the stock market. These securities are issued by an investment banker who assigns shares in publicly traded companies to the market maker, who records their ownership, in this case by the asset manager on behalf of the pension. The proceeds of the purchase, minus any fees, accrue to the companies in question. In the case of a stock sale, the process operates in reverse.

A company uses the proceeds from share issuance to support investment in real projects, such as a new factory or a wind farm. As a company’s stock price in the markets rises, it has more value on its books, increasing its ability to invest. The inverse happens as its stock price falls. As the map shows, capital projects may be funded not only by publicly traded companies but also by private corporations, both for-profit and non-profit, or any combination thereof.

Stewardship equity financing: the system

In a stewardship equity deal, the stock market is bypassed. A pension’s investment office enters into a membership agreement with the stewardship equity platform (SEP) which acts as both financial broker and project overseer. The SEP accepts the pension’s capital allocation, along with any fees or profit-share established under the membership agreement.

Capital projects

For capital projects, the SEP invests a pension’s capital allocation directly through financing agreements with participating enterprises. Projects are selected to align with the pension’s long-term investment horizon: an advanced geothermal power plant, a clean ammonia energy system, or a mission-driven social enterprise, to name a few. It doesn’t matter what the investment is, as long as it can guarantee returns over many years, and it aligns with stewardship criteria: avoiding extractive or exploitative projects, encouraging regeneration of planetary and social systems. With the SEP playing this role, there is no longer a need for a pension advisor.

To see this version of the system in the map, click the States icon in the toolbar (a cube) and select Future practice – capital projects.

Corporate acquisitions

What applies to capital projects applies, with a few tweaks, to a corporate acquisition. In the system map, select the state labeled Future practice – corporate acquisition.

Whereas a capital project might be funded by a single pension plan or a joint venture of a few pension plans, a corporate acquisition on the scale of ExxonMobil would require the participation of a consortium of many pension plans. Each would enter into a membership agreement with the SEP as an investor member in the acquisition. The SEP would form a subsidiary acting as the general partner in the deal, with the pensions as limited partners. Each pension’s membership agreement would specify its percentage interest in the acquired company’s stock.

Then the SEP would issue a tender offer for the target company through an investment bank. A tender off is a request to shareholders to offer their stock for sale during a specified window for a certain price, typically higher than market value. The mechanism is essentially just like any private equity deal for a corporate buyout.

Once the SEP has collected all the corporate stock from the market, it would file papers with the relevant exchanges to de-list it, taking it private.

Then the SEP would go to work to steer the company from non-stewardship activities toward stewardship ones. The company would gradually divest from extractive activities and invest in regenerative ones. It is unlikely this transformation would be accomplished in less than ten years, and could easily take twenty. Fittingly, it would be like trying to turn an oil tanker around. Many other factors would influence its timing and extent, such as competition from other companies, and legislative and regulatory environments.

Yet whereas in the past financiers have been guilty of using corporate buyouts to gut acquired companies and reward themselves fat bonuses at the expense of workers, this form of financial engineering serves the wider planetary purpose of stewardship.

Retail investment in stewardship equity

Now, in the system map, select the state labeled Future practice – retail investment.

This third future state sketches the role of retail investment in stewardship equity. It is twofold.

First, retail investors can participate in stewardship equity deals. This is where defined-contribution pensions get in on the action. People with IRAs or 401(k)s could invest in so-called ‘sidecar funds’ formed by retail asset managers. They would attach onto defined-benefits pension investments, much as a sidecar attaches to a motorcycle, thus forming a secondary market for stewardship equity investment. This secondary market should emerge once defined-benefits pensions had proven the viability of the stewardship equity model, thereby expanding the volume of available funds.

Second, as the map shows, the SEP could participate in the financial markets in its own right. This would simply be a form of arbitrage for short-term gain. The SEP could invest through an asset manager, although more likely it would establish its own trading desk. Forever money from pensions would continue to go into forever projects, but the SEP could use some of its own returns on forever investments to play the markets.

Stewardship equity financing: deal flow

Having mapped the players and the system, Tim and I developed additional system maps showing the deal flow. These maps form the framework of the financial model running the numbers.

Corporate acquisition

Above the Investing in Forever system map, click on the link InvestingInForever_Acquisition. This will launch the acquisition deal flow system map.

Phase 1: Pension investment for corporate acquisition

Upon launch, the map shows the first phase of the process, in which a consortium of pensions invests to acquire a target company, such as ExxonMobil. The pension consortium makes a capital allocation to the stewardship equity platform, which makes a fiduciary contribution to a retail asset manager for the buyout. Upon acquisition, company stock accrues to the pensions in the consortium and the SEP assumes oversight over the managing member of the company—that is, the company’s executive office, through a primary role on the Board of Directors. The SEP might even install new executives aligned with the SEP’s and pension consortium’s mission.

The SEP will set annual targets for the progressive retirement of non-stewardship activities and the growth of new stewardship ones. For ExxonMobil, this would entail the replacement of its oil and gas business with a new clean-energy business. In its Board role, the SEP would need to strike a balance between transforming ExxonMobil’s business as quickly as possible and establishing goals that company management can realistically achieve.

Phase 2: Allocation recovery

In the system map, click on the States icon and select Phase 2: Allocation recovery. This state reveals details of the enterprise itself and flows of money among the various parties.

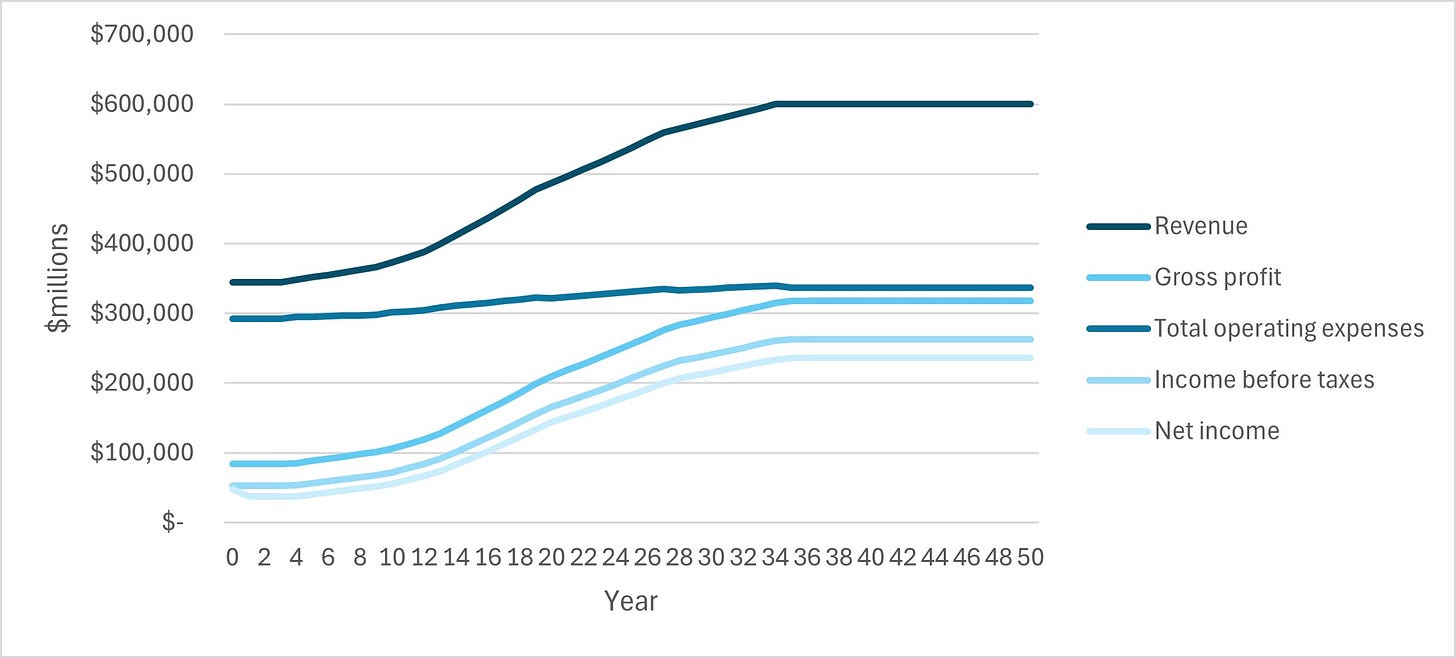

Anyone with a basic grounding in finance and accounting will recognize the flow of cash within the enterprise as a generic income-and-expenditure or profit-and-loss calculation. Costs are deducted from sales revenue, producing a net revenue known as ‘earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization’ (EBITDA). Taxes flow to the Treasury, and other deductions, as applicable, are subtracted from this. The net cash that results is free cashflow.

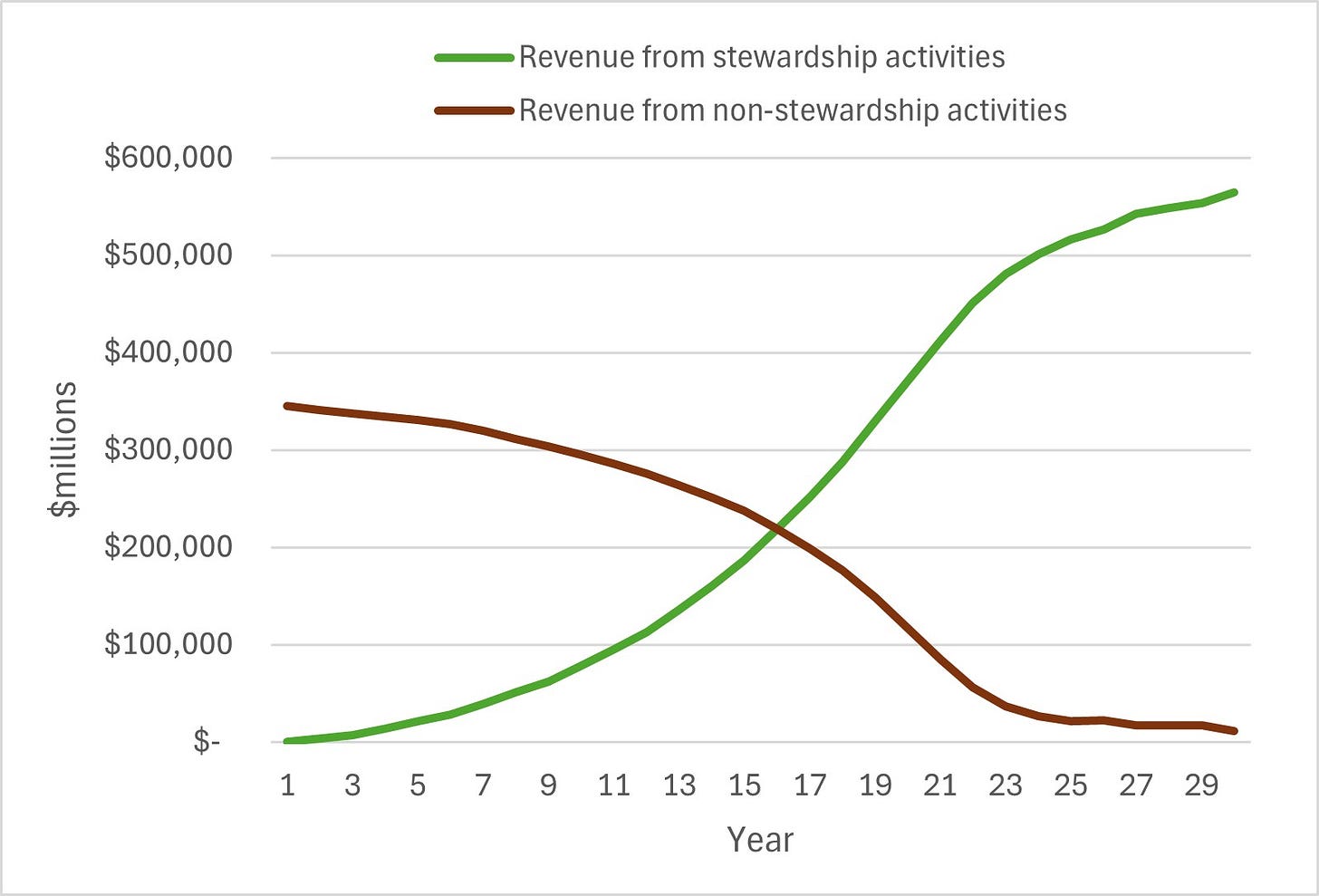

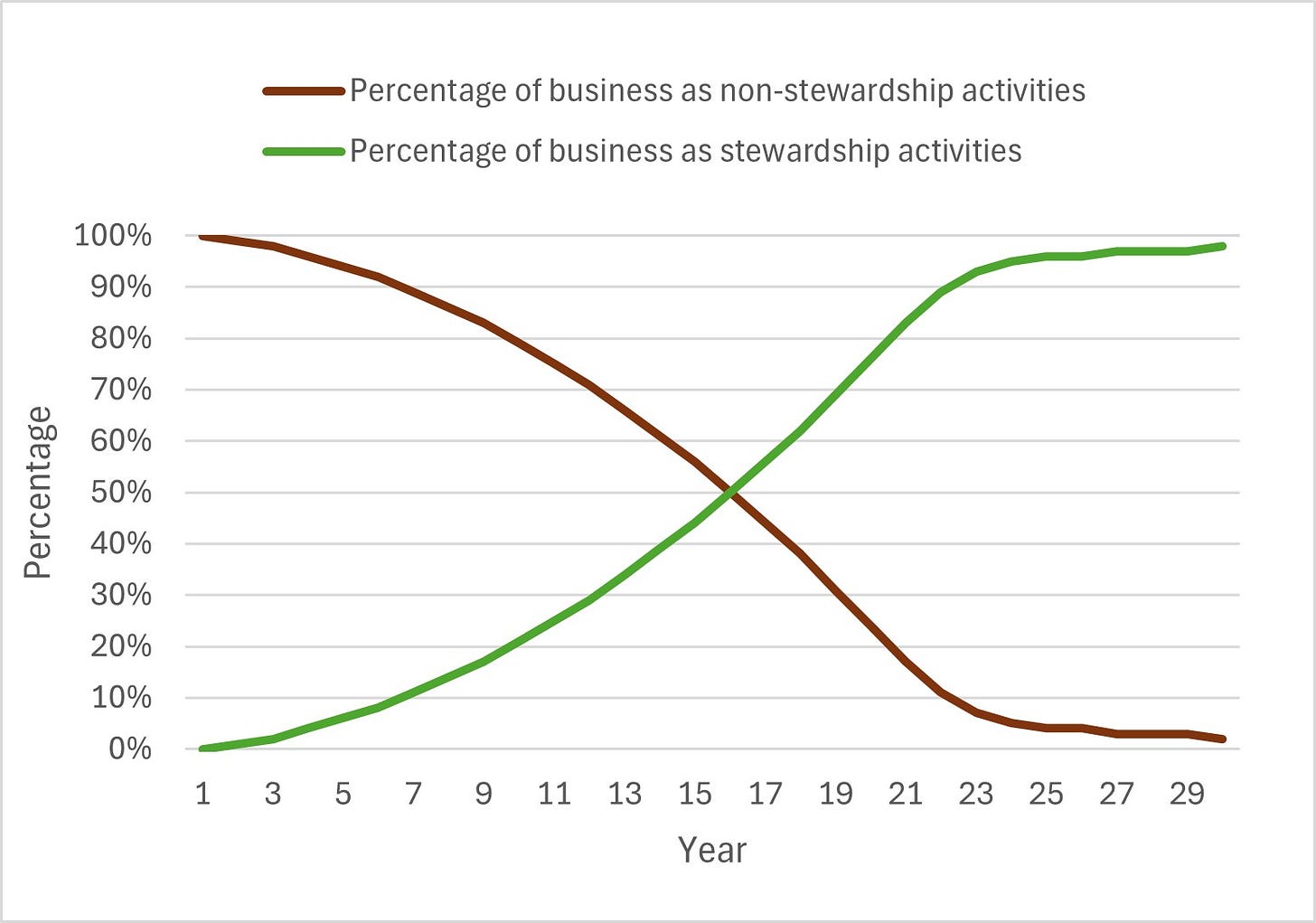

In the model, we enter starting values in year zero from ExxonMobil’s income and expenditures in its 2023 Annual Report.[6] Over time, the model reduces Exxon’s oil and gas activities and increases its stewardship activities. The transition follows an S-shaped curve over twenty years, as illustrated in figure 4 below. The model extends the profit and loss projection out over a total of 50 years to accommodate all conceivable payback scenarios.

During the early years after acquisition, ExxonMobil’s revenue growth is assumed to be minimal—less than 1 percent per year—as the company begins to reorient itself. However, as revenue from stewardship activities takes off, overall revenue grows at a higher rate—up to 3 percent between years 15 and 20. As the stewardship side of the business matures and extractive projects are retired, year-on-year growth in real terms tails off to zero by year 35. The company is now operating as a stable, forever enterprise.[7]

Ordinarily, free cashflow would accrue to the enterprise to reinvest or pay bonuses. However, the pensions in the consortium need to continue paying their retirees. So, until the pension consortium is made whole, most of the free cash flows into a so-called ‘sinking fund’ established by the SEP. During the allocation recovery phase, the model assumes that 95% of free cashflow goes into the sinking fund, with the remaining five percent to company operations.

This may seem like a paltry amount for the enterprise, but in ExxonMobil’s case the sums are huge: five percent of its free cashflow is about $2 billion per year. The actual equity split would be negotiated during acquisition, so these percentages are purely illustrative, yet they indicate the priority given to equity payback. Company executives should not expect bonuses during the early years. All available cash would be invested in the transition toward stewardship activities, such as repurposing oil and gas wells for geothermal energy.

From the 95% of free cashflow out of the enterprise, the sinking fund pays an annual return to the pensions equal to the initial capital allocation multiplied by their target rate of return. In the Exxon model, this is 6% on $582 billion, or $34.9 billion, out of an initial free cashflow in year 1 of about $35.5 billion. The remainder goes to the SEP.

The SEP’s annual fee—negotiated in the membership agreement with the pension consortium—is, like the consortium’s rate of return, a percentage of the initial capital allocation. In the model, this is 2 percent, or $11.6 billion per year. Net of administrative costs, which are tiny by comparison, all of it flows into a SEP investment fund for other stewardship ventures.

In the Exxon model, there are insufficient funds during the early years to pay the full 2 percent to the SEP after paying the pension consortium, so the model tracks the deficit to the SEP from one year to the next, and pays it back once free cashflow from the enterprise becomes sufficient.

Any surplus cash left over from paying the pension consortium and the SEP is added to the sinking fund balance. In the Exxon model, no such surplus appears until year 14 but then it grows quite quickly. The purpose of the sinking fund balance is realized in the next phase. Meanwhile, the SEP tracks how much of the initial capital allocation has been paid back from one year to the next. In the Exxon model, annual disbursements cumulate to the initial capital allocation by year 13. This allocation recovery triggers the next phase.

Phase 3: Cost of money and equity payback

Having paid out the initial capital allocation, free cash from the enterprise now pays back the pensions’ cost of money. In the transition year from phase 2 to phase 3, any cash left over from allocation recovery is carried into the cost of money phase. Click on the state for Phase 3: cost of money in the system map, and you will see this as a dotted arrow linking phases 2 and 3.

In an equity payback arrangement, the equity split between the enterprise and the investor can be a little more generous to the enterprise during the cost of money phase than in the allocation recovery phase. In the Exxon model, the enterprise now gets 10 percent of free cashflow, with the remaining 90% going to the sinking fund. As in the prior phase, the pension consortium continues to receive its $34.9 billion annual payout, and the SEP its $11.6 billion annual fee; yet now a surplus is flowing into the sinking fund balance.

From year 1, the SEP has tracked the internal rate of return on the initial capital allocation. This IRR is the total internal rate of return: that is, the pensions’ target rate plus the SEP’s annual fee. In the Exxon model, these sum to 8 percent (6% to the pensions, 2% to the SEP). During the early years, the IRR is strongly negative, but by the year of transition from allocation recovery to cost of money, it reaches 0%, this of course being the year in which the total annual payouts equals the initial capital allocation.

Thereafter, the IRR turns positive, as cashflow continues to pay the pension consortium and the SEP. Each year, the sinking fund balance grows, and the IRR approaches 8 percent. The model is structured so that the balance in the sinking fund matures to equal the initial capital allocation around the same time as the IRR hits 8 percent. In the ExxonMobil model, this event occurs in year 23.

At this point, the sinking fund has done its job. It has accumulated enough surplus cash to pay the pension consortium’s initial investment back. Remember that during all this time, the annual payouts—equal to the cost of money on the initial capital allocation—have been going to the pensions’ retirees, not to the fund itself. So equity payback, made as a single lump sum, renders the pensions whole. They can now invest their money elsewhere, having incurred no appreciable opportunity cost relative to investing in the stock market, and with lower risk.

Equity payback prompts the closing of the sinking fund and the end of the cost of money phase.

Equity upside

After that, it’s all gravy—or ‘equity upside’ for the three parties in the deal. In the system map, click on the States icon and select Phase 4: Equity upside.

By this point, the model version of ExxonMobil has remade its business, with more than 90% of its revenue coming from stewardship activities. The model assumes that after equity payback, most of the free cashflow would remain with the enterprise, this being its reward for paying back the pension consortium and becoming a good planetary steward.

In the ExxonMobil example, we assumed 80 percent would flow to the enterprise, 15% to the pensions and 5% to the SEP. With no equity payback to support, these become vast sums of money. In year 25, the company generates $183 billion in free cashflow on $538 billion in gross revenue. In reality, the company might reinvest a good chunk of that $183 billion; the model doesn’t capture this, but even if free cashflow were about one-tenth of gross revenue—which is in line with Exxon’s 2023 financials—these are still giant sums, almost all going to support further stewardship ventures.

Alternately, the enterprise could seek to buy out the SEP’s or the pension plan’s interests.

Capital projects

Above the Investing in Forever system map, click on the link InvestingInForever_Project. This will launch the capital project deal flow system map.

Whereas in a corporate acquisition, a pension consortium makes a capital allocation to begin the process, things are a little different for a capital project, such as a renewable energy facility. As the smap shows, phase 1 includes the actual building of a project even before a pension fund (or consortium of pensions) becomes involved.

In the example in the smap, a corporation (the ‘managing member’) finances the project through a loan. The SEP plays the role of guarantor. It enters into membership agreements with the pension plan and the managing member in charge of the project. The managing member can take the agreement to the bank—literally—because the bank knows its loan will be paid back, with interest, at commissioning.

The managing member typically will form a limited liability company for the project as a subsidiary. As construction milestones are reached, the bank releases progress payments until the project is ready for commissioning, when the proverbial ribbon is cut and the switch thrown. This is the event that triggers the pension plan’s entry into the deal. Its capital allocation pays off the loan and provides initial operating revenue until the project generates revenues of its own. Known as a ‘build-out to take-out’ model, it is by no means the only form of project financing available, but it is fairly commonplace in renewable energy projects, and it illustrates the roles of the SEP and the pension plan.

Thereafter, things proceed in the same way as in a corporate acquisition, as you can see by stepping though the states in the map.

Let’s talk about stewardship

Reporting in The Guardian, Oliver Milman has some surprising things to say about the Biden administration’s record on fossil fuels, given its much-vaunted record on renewables. On Biden’s watch, the United States’ lead over other petrostates in oil and gas production did not diminish, as one might expect, but actually increased. The US has become the world’s third largest exporter of oil and the world’s number-one exporter of gas. Under Biden—and this last one is really a shocker—the federal government has issued a record number of drilling licenses.[8]

Yet the US is not alone among wealthy nations in increasing production in the face of treaty commitments to reduce it. All wealthy economies are sufficiently diversified to have the capacity to move away from fossil fuels, yet today they are doing the opposite. Meanwhile, small, undiversified or low-income economies, whose carbon footprints are small, are stuck with no influence over the unfolding events on planet Earth. Since 2020, the world’s top six oil and gas firms, Including Exxon, have increased their capital expenditures by about 60 percent. There seems to be nothing people can do to stop them.[9]

This is why institutions with giant wads of cash and a duty to long-term care, such as pensions, are uniquely positioned to help not only their members but the whole world.

So what exactly is stewardship, and why are pensions uniquely placed to lead in it?

Anyone who, like me, enjoys watching soccer will be familiar seeing the people stationed around a ground wearing fluorescent yellow bibs labeled ‘Steward’. They’re there, of course, for crowd control. These are not the only kind of stewards. Indigenous peoples are often described as ‘stewards of nature’. Cabin crews on commercial flights were once more commonly referred to as ‘stewards’ and ‘stewardesses’.

The various usages of the word had me reaching for my Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. ‘Steward’ derives from the Old English, stig, probably meaning ‘house’ or ‘hall’, and weard, or ward. In other words, a steward is a house-ward or “an official appointed to control the domestic affairs of a household,” as the OED describes. It also notes various other meanings, such as an administrator or dispenser of wealth, an officer in a guild or corporation, an overseer or foreman, and an official appointed to maintain order at a race, meeting or show—hence the guys in the yellow bibs at soccer matches.[10]

In its modern meaning, a ‘steward’ can perhaps be boiled down to ‘someone who corrals and guides a crowd or an asset in a particular direction.’ The household connection is important as well, because the Greek for house, oikos, is at the root of both ecology and economics. Under an ethos of planetary stewardship, the ‘house’ in question is, by definition, Earth and everything on it.

Don’t divest: acquire and retire

According to Ian Edwards at Bank of Nature, “buying ExxonMobil is the opposite of divestment.”[11] All the calls in recent years for university endowments and pensions to divest from fossil fuels, even if successful, would not force oil and gas companies to leave what is a very lucrative business. So, rather than trying to remove them from institutional portfolios, let us instead welcome them into portfolios by taking control of them and converting them into regenerative businesses.

The system maps and accompanying financial model outline a well-understood mechanism to do this. It’s a win-win-win.

First, pensions would fulfill their fiduciary duty to the future well-being of their members by aligning their investment horizons with the long view of their beneficiaries.

Second, investing forever money in forever ventures is less risky than speculating in the financial markets. Executed prudently and judiciously, it will provide reliable, long-term returns to pension funds.

Finally, not only will pension holders benefit but also everybody else. Pensions and endowments are so vast financially, and unfettered by legislative inertia, that they can do what governments seemingly cannot, which is to expeditiously guide whole industries in a new direction, enabling and stimulating the regeneration of the ‘house’ that is Earth—encompassing both nature and human society. An acquisition of ExxonMobil and its conversion to a clean-energy company would create millions of new jobs along its supply chain. But much more significant than this, it would spawn all kinds of other spin-off investments. If a stewardship equity platform were to make $11.6 billion per year from an Exxon acquisition then that’s $11.6 billion to invest in other programs not needing a six percent rate of return. A basic income program for a million families at $1000 per month, for example. This is the essence of the original meaning of stewardship.

In the case of oil and gas companies, an ‘acquire and retire’ strategy represents a classic example of supply-side economics, in which the demand for energy is altered by changing the nature of its supply, from extractive to regenerative. The strategy would exert a domino effect on many other industries: transportation, construction, chemicals, to name a few. If you convert the oil and gas industry to clean energy, you’re converting almost the whole economy to clean energy.

How the strategy should be executed is an open question. If a consortium of pensions initially took a single oil and gas company private then, in embarking on its transition to stewardship, that company would find itself competing first against existing oil and gas companies still following the extractive model, and then later against clean energy companies. Its short-term prospects might be uncertain, even if its long-term prospects were rosy. Of course, pensions and other endowments theoretically have the financial resources to acquire and de-list all major oil and gas companies at once. One imagines that the companies might then compete with one another to be the best steward, thereby accelerating the process. There is no right answer. Pensions would have to try out the process on capital projects to test and refine it, before tackling an acquisition.

As Ian and Tim describe, unless humanity cleans house, nature will at some point hand it an eviction notice. Deploying pension and endowment money to acquire and retire extractive industries is a means—a very promising one—to forestall that notice. It is literally a way to save the world. From itself. All that needs to happen is for the money to pour in the right direction.

Endnote

The internal rate of return is the return on an investment at the point where a project reaches breakeven. Prior to that point, the net present value of all cashflows from the investment is negative. After that point, the NPV turns positive. The net present value is the discounted value of an investment at some future date, the discount rate itself being the internal rate of return. Breakeven occurs when the NPV equals zero.

where n is a period, such as years, N is the total number of periods, Cn is the cashflow in any period, and r is the internal rate of return.

The equation says that, for any IRR (say, 6 percent) there will be a certain point in the future at which the sum of cashflows over all prior periods equals the initial investment, discounted by the IRR. This is breakeven. The higher the discount rate, the longer it will take to reach breakeven.

Works Cited

ExxonMobil (2023) Annual Report. ExxonMobil Corporation, Spring, TX. https://investor.exxonmobil.com/sec-filings/annual-reports/content/0001193125-24-092555/0001193125-24-092555.pdf

Milman, O. (2024) The US’s quiet rise to the world’s biggest fossil fuel state. The Guardian, 24 Jul 2024: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/24/fossil-fuel-liquified-natural-gas-louisiana.

Milman, O. and Lakhani, N. (2024) Revealed: wealthy western countries lead in global oil and gas expansion. The Guardian, 24 Jul 2024: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/24/new-oil-gas-emission-data-us-uk.

OED (1993) The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, Fourth Edition, edited by Lesley Brown. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

[1] An allusion to the Red Queen’s race in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass.

[2] OECD (2024).

[3] These totals come from the OECD’s Asset-Backed Pensions – Main Database, accessible through the OECD Data Explorer, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/. Downloaded data were filtered to include both occupational and personal pension plans, across both defined-benefit and defined-contribution types. All data are in US dollars.

[4] ExxonMobil (2023).

[5] See Endnote for an explanation of IRR.

[6] ExxonMobil (2023).

[7] A variety of assumptions about the company’s long-term growth are possible; in this instance, we chose to err on the conservative side.

[8] Milman (2024).

[9] Milman and Lakhani (2024).

[10] OED (1993) p. 3955

[11] Ian Edwards, pers. comm.