September being the time of change, it’s been out with the old and in with the new. In the two weeks it took for the old guard of tennis to be swept aside by a 19-year-old Spaniard and a 21-year-old Pole at the US Open, Russian forces in northeastern Ukraine found themselves swept away by a lightning Ukrainian advance, and Britain acquired both a new prime minister and a new monarch within days of one another.

But I’m not here to dwell on such parochial matters. I am here to take the long view, foretelling the demise of the old and the rise of the new over a period of decades. Specifically, I am here to give advance notice of the death of capitalism. Yes, you’ve probably heard that before (not least from Karl Marx) but bear with me here. By the time society accepts that capitalism really is dead, perhaps around the end of this century, we will live in a world operating under an altogether different economic doctrine. What it will be, and how it will arise, are the subjects of this article. It’s a longer read than most but, I hope, worth it.

Something is wrong with the economy

In the 1860s, a Dakota boy asked his uncle why the white man committed so many atrocities against the Native Americans, taking their land and murdering whole villages. “The greatest object of their lives,” his uncle replied, “seems to be to acquire possessions—to be rich. They desire to possess the whole world.”[1]

That desire is symptomatic of, and a feature of, modernity, a world-view that emerged in Europe during the scientific revolution, which, in turn, enabled the industrial revolution. The subject-object dualism, originally articulated by René Descartes (1596–1650), was foundational to the emerging scientific paradigm, enabling as it did a cognitive separation of the individual from their surroundings and, with it, objective experimentation. This was a remarkable break from the medieval world-view, in which things were seen as part of an interconnected whole. As Descartes himself noted, the subject-object separation had practical value in harnessing natural phenomena for material gain, thereby “[making] ourselves masters and possessors of nature.”[2]

These words revealed modernity’s cognitive disconnection from the natural world and, with it, a lust for dominion. Nature is a resource to be exploited for human enrichment rather than a foundational life-support system. The Cartesian world-view is an example of what Morris Berman called a ‘nonparticipating consciousness’. Viewed within the whole sweep of human history, this consciousness is an anomaly, distinguished as it is from the ‘participating consciousness’ of the vast majority of peoples at all times and places prior to Descartes, and of most indigenous peoples today. In a participating consciousness, humanity is perceived as embedded within nature.

The modern economy and society are unequipped to deal with the consequences of their effects upon Earth’s natural systems and of nature’s reactions in turn upon them. Worse, our economy encourages the accumulation of disproportionate wealth in the hands of the few, despite generating more than enough wealth for everybody. The moral implications of these failures, serious though they may be, pale, however, in comparison to the risks they pose to the stability of the economy itself, whether through surprises from nature or social unrest.

The root of the problem lies with the capitalist system’s rewarding of the accumulation of capital. Left unchecked, this reward structure degrades both nature and society. The 20th-century’s principal alternative to capitalism, communism, had an equally poor record in this regard, the only significant difference being that capital accumulated to the state rather than to individuals.

The accumulation of capital is not unique to capitalism: after all, people in positions of power had been accumulating capital for centuries, But capitalism, as an economic doctrine, in a sense democratized the accumulation of capital. Now, anyone and everyone could try their hand at it, no matter where they came from. In older, feudal societies, everyone knew their place, even if perhaps grudgingly; now, under capitalism, it was everyone for themselves. Descartes’ dualism provided a basis for so-called ‘Enlightenment’ philosophers, such as John Locke and Samuel Bentham, to proclaim the individual as paramount. Capitalism set off an arms race of competition for resources. Add the accelerant of industrialization, and we arrived at the extractive economy of the 20th century, in which hardly anyone was paying attention to the planetary consequences of their greed. Aside from a brief dip during the three decades after the Second World War, this greed produced an inexorable increase in wealth inequality to a point where, today, the world’s wealthiest billionaires own more assets than the bottom fifty percent of the human population, about four billion people.

If we originally lost our participating consciousness to science, should we try to get it back? Should we reject science for spirituality, or for something else? No. A middle road exists, and it is the way forward for global society, as it stumbles through the 21st century. The philosopher Gary Snyder put it most aptly in a 1969 article:

What we envision is a planet on which the human population lives harmoniously and dynamically by employing a sophisticated and unobtrusive technology in a world environment which is ‘left natural’. […] Master the archaic and the primitive as models of basic, nature-related cultures—as well as the most imaginative extensions of science—and build a community where these two vectors cross.[3]

In other words, re-embrace the wisdom of a participating consciousness—which, among other things, unravels rampant wealth accumulation, spreading it around—and put the best of our scientific and technical abilities to work to fashion a society that is as unobtrusive as possible upon planet Earth.

It is as if, having been trapped for so long in a feudal system, European society after the 15th century went too far the other way, and now, five hundred years later, the pendulum needs to swing back toward the center, to recapture some of the old ways of perceiving and thinking about the world. In this, Western society has much to learn from indigenous wisdom, which fortunately, although by the skin of its teeth, survived the eruption of European colonialism, a horror fueled by the very same Cartesian doctrine that powered the scientific revolution.

Capacity, not capital

In my recent books, Economics of a Crowded Planet and A Planetary Economy, I asked the question, given what we currently know about the interaction between the economy and Earth’s natural systems, how would economics or the actual economy look if we started with a blank sheet of paper?

The examination of this question brought up the concept of ‘capacity’, which is commonly used in ecology to describe how populations grow and ecological communities develop. For any species within a community, a ‘carrying capacity’ can be defined as a limit on the number of individuals of that species the community can accommodate. Carrying capacity is never constant; it fluctuates as environmental conditions change. It is, nonetheless, an instantaneous measure, a point estimate.

Yet ecology also employs another, dynamic, concept of capacity. In the 1960s, Howard Odum applied principles of electrical circuit flow to ecological modeling, devising a typology of ecological processes incorporating concepts of switching, resistance and capacitance. Real ecosystems exhibit patterns of storage and release, such as of nutrients or minerals, which can be described using Odum’s energy circuit language. But the interesting part of all this is that Odum then applied the energy circuit language to interactions between ecosystems and human systems, showing how they influence one another materially.[4]

Building on Odum’s work, I developed a model of nature and the economy incorporating a dimensionless measure of nature’s capacity to support the economy, which was pegged to the probability of the economy’s collapse over a given period, say, 200 years. We can’t actually measure nature’s capacity to support the economy in material terms because there are so many unknowns. But, for the purpose of running scenario analyses, one can make a reasonable assumption that if ‘natural capacity’, as I called it, became sufficiently degraded then the probability of economic collapse some time within the next 200 years would be quite high.

The model itself, and the results it produced, are chronicled in Economics of a Crowded Planet for any reader who wants to geek out on the details—or, for that matter, critique the model and suggest improvements. The important thing here is the concept of ‘natural capacity’ because it suggests a way to escape from the language and doctrine of capitalism toward a new way of thinking about the economy’s—and society’s—relationship with planet Earth.

Ever since the beginning, economics has treated nature as a form of depletable capital. The writings of Adam Smith and David Ricardo were a product of their time: a ‘modern’ society whose members perceived themselves as ‘masters and possessors of nature’. To Ricardo, ‘land’ was a capital asset whose productive capacity could be exploited for economic gain. Two hundred years ago, the size of that capital asset was perceived as essentially limitless.

The imposition of the term ‘capital’ upon nature, however, was the lazy application of a financial term to a collection of physical and biological systems where it had no place. The concept of nature as a stock of capital failed to accommodate its actual status as a complex system. The capital concept equally failed to acknowledge the economy as a complex system, as a matter of fact. It would be more appropriate to go in the opposite direction, applying concepts from systems sciences to nature and the economy.

To see how, we need to begin, ironically, with the analogy of a bank account. A bank account contains a stock of capital, measured in money terms, from which the account holder can withdraw funds. A withdrawal represents a flow of capital to the holder as income. The addition of capital to the account from an external source, such as from rent or earnings, also qualifies as income. The difference is that a withdrawal depletes the capital base, whereas a deposit increases it. The capital base also can increase through an accrual of interest paid by the bank.

In economics, the distinction between capital and income was first recognized by Irving Fisher, who pointed out that a flow of income from a stock of capital must necessarily deplete it. This point was subsequently lost on mainstream economists, who valued natural inputs to economic production as a stream of free income, reflecting their long-held assumption of nature as an unlimited store of capital.

In the 1980s, ecological economists strove to correct this error by stating that the ‘income’ from nature comes at a ‘cost’ of the depletion of the base of ‘natural capital’. But Fisher never meant to apply the capital-income distinction to natural resources. His focus was on artificial capital, the capital of the economy.[5] By extending the Fisherian definition of ‘capital’ to include nature, the ecological economists made an implicit assumption that nature has the property of economic capital, where it does not. Nonetheless, the concept of ‘natural capital’ made its way into international accounting systems, fitting as it did conveniently into established accounting conventions.

The key distinction here is that whereas a stock of economic capital is inert, nature is autopoietic: that is, self-generating. It lives. Although a farm harnesses nature to make food, its classification as a ‘capital asset’ in an accounting sense does not suggest any living force. The concept of a ‘capital asset’ is a human construct to describe and value artifacts or real property. The autopoietic part of a farm is all of the living ecology within its property line. Some elements of a farm’s natural production, such as cabbages or onions, are perceived as useful. Others, such as weeds or insect pests, are not. To a farmer, ‘useful’ biological production has economic value, whereas ‘useless’ biological production does not. There is no market for weeds, yet nature produces them anyway, even though they may place a cost upon agricultural production. Weeds, by definition, must serve some other, non-economic purpose.

The fallacy of the concept of ‘capital’ is further exposed when one considers effluents from economic activity. When effluents are released into nature, no stock of capital, as such, is depleted. Rather, effluents from the economy incur a material loading upon natural systems, which alters their dynamics. Howard Odum’s contemporary, Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, recognized this fact in a thermodynamic treatment of economic processes.[6]

The distinction between ‘capital’ and ‘capacity’ is fundamental. They are as different as a car and a tree. A car is a capital asset that will depreciate over time whereas a tree is self-replicating. The concept of ‘capital’ is static and subject to mechanical analysis. As such, it is reversible over time. The concept of ‘capacity’ incorporates time as a variable, which makes it historical, and therefore not reversible, only reattainable. ‘Capital’ may be treated analytically as an exhaustible stock, subject to the marginality theory of standard economics, whereas ‘capacity’ conforms to a growth function or to logarithmic capacitance. The growth of capacity can indeed create capital, just as a capacitor can accumulate electrical potential, but as capital becomes liquidated, capacity must continually regenerate it.

Nature is not a stock of capital, like a bank account, but a source of capacity: a system of producers and consumers. Inputs to the economy from nature are the products of systems that, like manufacturing processes within the economy itself, assemble simpler components into more complex, useful resources. In the same way that it is impossible to take more from a factory than it can produce over a certain time, it is impossible to take more from living systems than they can produce over time. Nature does not provide overdrafts. The size of a productive resource, be it a factory or nature, is important insofar as it determines its productive capacity: a larger factory can produce more goods, or a larger fish stock can yield a greater harvest. But the size of the stock is not, in itself, a measure of its ability to support human consumption. Similarly, on the output side, nature, as a consumer of effluents from the economy, has a certain capacity to absorb and process those effluents over time. The larger the natural capital stock relative to the economy, the larger its capacity to support economic consumption; but it is the absorptive capacity of nature, not its absolute scale, that measures its ability to support the economy.

Replacing the static concept of ‘capital’ with the dynamic one of ‘capacity’ allows both the input and output sides of the relationship between the economy and nature to be considered on the same terms. The dynamic quality of capacity also necessitates a recognition that changes to nature arising from the material intensity of the economy will not resemble linear adjustments to capital stock, as in accounting. They will more likely be non-linear, unpredictable, even non-repeating, because both nature and the economy are complex, evolutionary systems.

A concept of ‘natural capacity’, as a replacement to ‘natural capital’, necessitates a systems view in which the economy and nature coevolve. The problem with applying the term ‘capital’ to nature is that it implies all the accumulated material in nature being available to society for expropriation, like the drawing-down of a bank balance. The term ‘capacity’, on the other hand, implies flows of material to and from nature. These flows cannot exceed nature’s capacity to accommodate them, in order for nature to continue to support the economy.

Nature’s capacity to support the economy derives from its autopoiesis which, in turn, is powered solely by free energy from the sun. Thermodynamicists call this energy ‘free’ because it comes to Earth at no cost, energetically or otherwise. While Earth, in this sense, is energetically ‘open’, it is materially closed. The economy relies wholly and completely upon finite material circulation. Whereas solar flux is practically unlimited, being continuous and more abundant than the economy will ever need,[7] all other natural inputs to the economy carry costs because they are endogenous to Earth. Solar energy also powers nature’s absorptive capacities for economic effluents, but again, those capacities are materially limited. Viewing nature in capacity terms implies material flows among systems, by definition, and therefore the coevolution of the economy and nature.

Capacitism

The name of the game, then, for the long-term persistence of the economy and of the society it supports, is the maintenance and enhancement of natural capacity. How does that look? How do we know whether we are on the right track or headed for economic collapse?

The early years of the 21st century have witnessed the emergence of various efforts to rein in humanity’s resource-loading upon natural systems, whether in the form of deforestation, greenhouse-gas emissions or plastic waste. Since the late 20th century, public attitudes toward these problems in developed countries have undergone a clear shift, from broad disinterest in the idea of protecting natural systems ‘for their own sake’, to an emerging appreciation of the tangible threat to the economy and society from abusing nature.

So far, these efforts have enjoyed mixed success; however, broad social and political momentum to address them is growing. Over the next couple of decades, we should expect significant progress in reducing anthropogenic resource-loading. But is is also a feature and a shortcoming of modern society that threats from nature are a more compelling reason to pay attention to it than the mere fact that it exists at all. In other words, a latent cognitive shift is waiting in the wings that would really transform society’s relation with the planet.

For now, an instrumental shift is sufficient to get the ball rolling. Indeed, it signals that modern society has forced upon itself the realization of the need for reform, which is itself an instrumental undertaking. Governments are curtailing extraction, regulating waste, and setting deadlines for industrial change. Not everywhere, nor yet across the board, but that process will only gather pace over time.

In my books, I give a name to these and future efforts: material discipline. A program of material discipline is the first step toward a capacitist economy, and it is also what would maintain that economy over time. Yet it is only the minimum condition for such an economy to emerge. As we shall see later, other, more fundamental societal changes also must occur for capacitism to truly flourish.

Because Earth is materially closed, the resource-loading of the economy upon nature is a direct function of its material intensity: the amount of stuff flowing into the economy from nature and the amount of stuff flowing out. An inverse relationship exists between the economy’s material intensity and Earth’s natural capacity—its capacity to support the economy. An economy treading lightly on Earth, in material terms, would become ‘unobtrusive’ in the way Gary Snyder imagined. Earth’s natural capacity would be correspondingly high, as seen in low measures of pollution, widespread ecological regeneration, and incipient climate stabilization.

Increasing material efficiency means reducing the volume of inputs and outputs, and recirculating as much material as possible within the economy. Among a myriad other undertakings, primary deforestation would be halted, greenhouse-gas emissions would be minimized, and synthetic, disposable plastics would be replaced with biodegradable alternatives and widespread material reclamation.

Old, extractive industries will die and new, regenerative ones will replace them. This process is already under way in some sectors, as we see in the incremental replacement of fossil fuels with renewables, for example. But this particular replacement has struggled against fossil-fuel incentives and political resistance. It would exponentially accelerate if the incentives were shifted from fossil fuels onto renewables. Of course, such an instrumental change by itself would cause immense disruption if implemented in one fell swoop. It would have to be accompanied by other governmental interventions to ensure that jobs lost from the dying industry would be picked up by emerging ones.

What we are witnessing in the early 21st century are the first signs of economic reform toward material efficiency. A formal program of material discipline, analogous to programs of fiscal discipline, would generalize the push for material efficiency across all sectors of the economy. It would represent a political and social acknowledgment that capitalism is inherently extractive and destructive, and that capacitism, in prioritizing the maintenance and enhancement of natural capacity, is inherently regenerative, therefore constructive for the economy and society in the long run.

This is not to reject all the features of a capitalist, market economy but it does reject the dogma of market fundamentalism, the idea that the market reigns supreme and should be allowed to do what it wants. Instead, economic policy now becomes teleological—that is, goal-directed—with the goal being material efficiency. To borrow a phrase from Star Trek, material discipline becomes a ‘prime directive’.

A market-planetarian economy

If capacitism is an economic doctrine of the maintenance of capacity—as distinct from the accumulation of capital—then it could, in theory, take a few different forms. Capacitism could be centrally planned, like the old Soviet economy, or it could be decentralized and community-based, as practiced by thousands of small communities throughout history. No doubt other forms of capacitism could be dreamed up. But today’s global economy is largely market-based, highly interconnected and capitalist in nature, so this is the economy we have to start with. The good news is that it happens to possess certain useful properties that can accelerate that transition.

The foremost of these is the market itself. Markets have power to unleash rapid economic change, given the right incentives. Imagine how quickly the agriculture sector could transform from industrialized, pesticide-dependent monoculture to organic polyculture and high-density vertical farming if the incentive structure were reversed. There’s more to it that this, of course, because consumers would have to be made indifferent to potentially higher prices at the store, but we’ll get to that. The point is that the market, having thousands or millions of distinct actors, possesses a kind of collective intelligence and decision-making ability no centralized politburo ever could.[8]

Whereas under capitalist doctrine, government took a largely hands-off approach to the market, under capacitism it would take a hands-on approach. This approach would bear some similarity to—take a deep breath here, Western capitalists—the planned market economy developed by China over the past few decades. This is not to defend China’s autocratic political model—quite the contrary, in fact—but to cite an example of an economy that is actively steered in directions perceived as desirable by its government, encouraging the development of certain industries and the emergence of their associated markets, while discouraging others. It is to put the economy ‘on a mission’ as Mariana Mazzucato describes.[9]

Imagine how differently things could have gone in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union if the market transformation in that country had been planned with a particular goal in mind—say, a broadly prosperous liberal democracy with strong institutions and little official corruption—rather than the free-for-all it was. Few Russians might have reminisced for the predictability of the old Soviet Union, or resented what was lost—sentiments on which Vladimir Putin subsequently gained significant political traction.

The fact is that the day communism died was also the day the death knell rang for capitalism, although to many in the exultant West this was not apparent at the time. Capitalism had ‘won’: there seemed no reason to critically examine where it was already going dangerously wrong.

A guided, market-driven capacitist economy is what I call a market-planetarian economy. It is a global economy, as ours is today: a collection of interconnected markets trading locally, regionally and globally. However, as a ‘planetarian’ economy, it betrays a societal awareness of the necessity for economic activity to align with natural systems. A planetarian economy is the work of a planetary-aware society. Rather than taking a commodity view of nature, planetarians take a regenerative one. They “view themselves from within the biosphere rather than on top of it,” as Peter Berg described when he originally coined the term. They “are anxious about maintaining distinct regions, cultures and species, and look forward to experiencing full ranges of planetary diversity without destroying them.”[10] They think about the needs of the whole planet in addressing any short-term, individual needs.

Planetarianism represents a huge cultural shift from Western modernism, as I describe below. A member of any indigenous culture reading this probably would say, “that’s what we’ve been trying to tell you all along”, and they would be right. Ranchers in Amazonia view the Amazon as “ours to burn”[11], a sentiment betraying not only a commodity view of nature but also a Cartesian, rather than holistic, view of the world, a non-participating consciousness whose folly is to somehow place humanity outside nature. If so, where? Cognitively speaking, if you throw something ‘away’, you also are ‘away’.

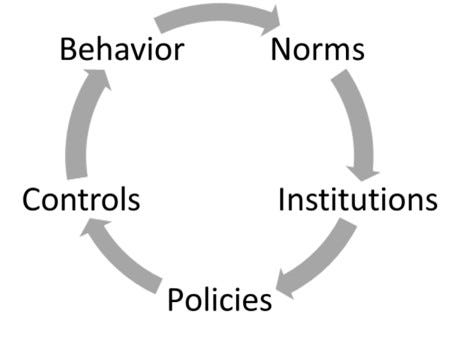

That cultural transformation might, from where we sit, seem impossible, or impossibly far away. Admittedly, it will probably take a few generations to attain, but it is eminently feasible. It begins with the realization, which has already dawned upon modern society, that economic intensity is bumping up against planetary capacity, prompting planetary reactions. This realization represents a new norm: it is normal today, where twenty or thirty years ago it was not, to admit that human activity is having global effects. The next logical step is to decide what to do about it, which is where we are now in the 2020s. What we do is to begin reforming the economy through a program of material discipline, progressively increasing its material efficiency. This necessitates not only new policies but also, in certain instances, new institutions: new ways of organizing decision-making. A recent example is the new US Green Bank, authorized and funded by the Inflation Reduction Act.[12]

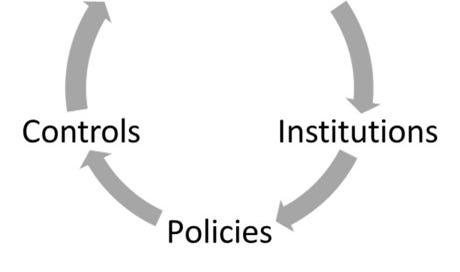

The process is iterative, as illustrated in the cycle below.

New norms produce new institutions, or reforms to existing ones. These in turn enact new policies that establish new controls upon the economy, or changes to existing ones. Controls steer the behavior of actors in the market in new directions, encouraging desired changes to economic sectors and markets, discouraging undesired ones. Within this altered economic landscape, over time, emerge new norms, which continue the cycle.

In a capitalist system, the cycle produces what could be described as a random or quasi-random economic drift, because no overarching directive exists to steer the economy in a particular direction. In a capacitist system, the economy no longer drifts: it is directed toward a goal of alignment with nature. So who, or what, does the directing? The answer—indeed, the only possible answer—is government.

Now this brings us to a crucial question not yet addressed, which pertains to ownership. If natural capacity is what enables the economy, then who speaks for it? After all, natural capacity is global, but humanity is divided into a collection of anachronistic nation-states. In A Planetary Economy, I go into some detail about governance, but suffice to say here that natural capacity is, and should be, stewarded by government on behalf of everybody. Natural capacity is a form of what Peter Barnes describes as ‘universal property’[13], which is, by definition, owned by everybody. It is the obligation of government to steward it: that is, to protect, safeguard and manage it for the common good into perpetuity.

But there is more to the role of government under capacitism than simple stewardship, and this where another advantage of a market-planetarian system becomes apparent. All enterprises in our economy, whether operating for profit or not, use natural capacity in the course of their daily business. Think about all the material goods a business or governmental entity needs to operate: these come from supply chains stretching back either into nature or to the outputs from material recycling. Similarly, all the effluents a business produces either end up in a recycling loop or back out in nature. Businesses pay for their material inputs, and for commercial recycling services, but they pay little if anything for the natural capacity that supports the inputs from and outputs to nature. This is arguably capitalism’s—and modernity’s—most colossal omission.

Conceptually, a superb way to place the economy on a fast-track toward material efficiency is to require enterprises to pay for the natural capacity they use. Essentially, government would rent natural capacity, on behalf of the people, to private and public enterprise.[14] The rents themselves—which we could call common capacity fees—need not be onerous but they should be noticeable enough to prompt businesses to change their practices to reduce material intensity. Because the present economy is so materially inefficient, there is enormous upside to generate trillions of dollars in revenue, not to mention also jobs and innovation, from these humble common capacity fees. If politically expedient, it would be straightforward to offset any burden from these fees with corresponding reductions in corporate taxes.

Revenue would be reinvested in promoting material discipline, or in other ways, described below. The important concept here is that the role of government in this market-planetarian form of capacitism is to rent capacity upon which enterprise generates wealth.

Both Barnes and I argue that a new institution would be required to undertake this role, so that government’s stewardship of capacity would be insulated from the vagaries of party politics. A ready-made institution already exists: the trust. This particular one would be a ‘planetary trust’.

Would individual people also be charged rent for their use of capacity? There would be no need. Businesses would pass along any changes in the prices of their goods and services, in whole or in part, to the consumer. Also, the portfolio of goods and services available to the consumer would itself transform over time. Few if any groceries would come from industrialized agriculture. Gasoline and natural gas would become expensive and, eventually, increasingly scarce, whereas most vehicles would be emission-free, and homes would be heated and cooled electrically. The challenge would be to ensure that substantially all consumers had the means to adapt to these changes. And, like all challenges, it presents an opportunity.

Indeed, it is a feature of a capacitist system that it maintains and enhances not only the capacity of nature to support the economy but also of the economy to support its people. The government’s obligation of stewardship, therefore, is twofold. It is responsible not only for the prime directive of material discipline but also for a second directive of widespread prosperity.

If large numbers of people were left behind by a program of material discipline because they did not have the means to keep up with it, the program would fail. Material discipline will succeed only if substantially all actors within the economy—businesses, government and consumers alike—are able to participate in it. Full participation is an absolute prerequisite for capacitism to replace capitalism; in fact, it is a defining trait of capacitism that capitalism lacks.

In practice, this means is that everybody must have enough money to afford the many changes that will unfold in their lives: from the food they buy to the heating and cooling of their dwellings, to the way they get around. This means a fundamental rethink about the distribution of wealth: who deserves it and who does not.

On a crowded planet such as ours, in which the global economy’s effects upon nature are causing reactionary effects from nature back onto everybody, there is really nowhere to be ‘left behind’ any more. Hardly any community—even the few remaining uncontacted tribes in the Amazon—will remain untouched by the changes already in train to Earth’s climate, ecology and other systems. A few billionaires, exhibiting their bunker mentality, have built actual bunkers in the misapprehension that they would provide safe haven during what they perceive as an ‘inevitable apocalypse’, but this exclusionary approach is doomed to fail. In the event of an economic collapse, the bunkers would be overrun. The only way forward—for rich and poor alike—is an inclusionary one. Sorry for the cliché, folks, but on a crowded planet, we’re all in it together, whether we like it or not.

Modernity is a culture of individualism. Planetarianism, by definition, is a culture of the collective, the ‘collective’ in question being all people on Earth. It follows logically that, for the collective in this sense to fully participate in a program of material discipline necessitates everybody to have at their disposal a minimum of wealth to afford it. You can see where this is going: basic income.

But here’s the sweet part about how basic income would be funded: through the common capacity fees paid by businesses for the use of capacity. In fact, as Peter Barnes describes, businesses currently use all kinds of other universal property free of charge: the internet, the electromagnetic spectrum, the electricity grid, the financial system, and transportation networks, to name a few.[15] In other words, mirroring the natural capacity that supports the economy, there exist various kinds of artificial capacity on which the economy depends, for which businesses could be charged small fees per unit of use.

Rather than the frayed ‘social safety net’ providing barely sufficient protection against poverty in only a handful of developed economies, a basic income scheme funded by common capacity fees would create an impermeable, concrete floor upon which everybody could stand. As I describe in A Planetary Economy, another complementary source of funding for basic income would be so-called ‘sovereign money creation’, the details of which extend beyond the space available here, except to say that government has the unique ability to insert new money into the economy for the purpose of goal-directed investment, as many did during the Covid pandemic, and to reabsorb any excess through taxation. Higher-income countries could quickly institute basic income funded these ways through legislation. A Planetary Economy offers suggestions for extending basic income to lower-income countries.

Basic income is only part of the story. Money, as a means of valuing and exchanging diverse commodities, circulates endogenously within the economy, the volume of that circulation being finite. This means that for every billionaire there are countless thousands or millions of people whose full economic potential remains unfulfilled. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that capacitism should require the abolition of billionaires but it would be very difficult to become one. A market-planetary economy would have to strike a balance between rewarding talent, innovation and initiative on the one hand and maintaining a moderate distribution of wealth on the other. Too flat a distribution of wealth, as existed under communism, would stifle innovation. Too wide a distribution of wealth leads to social resentment, disconnection and unrest, as in today’s economies. A ‘Goldilocks zone’ of wealth distribution exists where the top ten percent have perhaps a few times as much as the bottom ten percent.

In the early years of a transition toward capacitism, the people at the top might complain about having to pay for what they perceive as the ‘indolence’ of the people at the bottom, but what they would actually be paying for—whether through progressive income taxes or other means—would be the full participation of everybody in a capacitist program and, with it, their own long-term prosperity. Furthermore, if basic income were funded largely through common capacity fees or sovereign money creation, rather than through income taxes, then various mechanisms could be established for the ultrawealthy to exercise flexibility in the disposition of their excess income, as A Planetary Economy describes. Economic collapse, if it happens, will take rich and poor alike but economic stability, through alignment with nature, will make everybody rich, relatively speaking. Anyone who can claim a net worth of a billion dollars or more would live quite happily on a tenth or a hundredth of that.

A planetary society

Today’s society is ‘global’, in the sense that everybody knows where everybody else lives and virtually no unexplored places exist any more, at least on the surface of the planet. With the advent of the internet, search engines and social media, it has become possible to connect with just about anybody, anywhere.

But our ‘late-modern’ society, if we could call it that, is not yet interconnected in a cognitive way, nor indeed in a programmatic or teleological sense. There is not yet a shared acknowledgement of the placement of the economy and society within Earth’s natural capacity, as distinct from outside it or separate from it. Late-modern society is not holistic, whereas an early-planetarian society to come later in the 21st century might be.

The pendulum needs to swing—and indeed is beginning to swing—back away from the hyperindividualism of modernity, as exemplified by the settler-colonialist worldview, toward a new form of collectivism. Not the communist kind, which demanded mass conformity, but something fundamentally different: a recognition of the planetary collective. The pursuit of planetarian ends—harmonious coexistence with nature and guaranteed standards of prosperity for all—I believe will prompt a flowering of innovation, creativity, wealth-generation and diversity.

If initial steps undertaken over the next ten to twenty years are successful then, within about two hundred years, it is possible to imagine a planetarian society that will have largely fulfilled the two directives in question. How would it be to live in such a society? I imagine it would, first and foremost, be tranquil. Earth’s population of about eleven billion would live in relative prosperity: little if any outright poverty would exist, while at the same time no-one would be obscenely rich. Lands once carved up by agriculture or ranching would be reclaiming their lost ecology. Populations might be more highly concentrated than today, but cities and towns would be, if not all green, then at least heavily planted. With basic needs assured—and here I mean not only income but potentially also healthcare, education and housing—social resentment would be minimal and crime rates would be low. Wage-based employment would supplement basic income, people probably would work fewer hours than today, and employers would be under no obligation to pay anything other than wages.

Being a market economy, we would still see competition and innovation, although the profit motive might be correspondingly weaker, with other measures of success taking more weight. A planetarian economy might circulate several or many forms of currency, of which money would be only one. Others perceived as comparably important might be ideas, knowledge, time or status.

That said, such a society would find itself in the midst of dealing with, and adapting to, the mistakes of the past. The climate likely will be warmer and more tumultuous; sea levels will be higher; some regions might have become physiologically uninhabitable, while others became more productive. As I speculated in It’s Russia Jim, but not as we know it, the populations of large northern countries, such as Russia or Canada, could increase by a factor of ten under mass climate-migration. Fortunately, they don’t lack land to accommodate people, but the upheaval would be profound nonetheless.

Of course, this is an idealized vision of a planetarian society, a best-case scenario. It is important to keep these visions in the forefront of our minds because it would be all to easy for planetarian goals to become lost amid political bickering or social unrest. There will be a storm before the calm, for sure, and there is no guarantee that society will survive that storm. If we don’t, we can expect economic collapse and, with it, population collapse probably some time within the next two hundred years. Then humanity would have to start all over again, humbled and perhaps a little wiser.

Human beings are not ‘masters and possessors of nature’ but, when it comes down to it, gardeners. We are actually quite good at gardening: people have been pottering around their local ecosystems for millennia, shaping them to their benefit while maintaining their capacity to support their little communities and learning from their mistakes. Now we have to begin gardening the whole planet. This necessitates an attitudinal shift: that the garden calls the shots, you do not. If you mess up the garden, there is nowhere else to obtain sustenance, so it’s important to pay attention to and respect the signals the garden sends.

Capitalism is dead! (Or at least it soon will be.) ‘Modern’ society has run its course and can now be considered passé. It is time to give birth to a planetarian society and its accompanying economic doctrine of capacitism.

Works cited

Barnes, P. (2014) With Liberty and Dividends for All. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

Barnes, P. (2021) Ours: The Case for Universal Property. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

Beinhocker, E.D. (2006) The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Berg, P. (1978) Globalists versus planetarians: an interview of Peter Berg by Michael Helm. In The Biosphere and the Bioregion: Essential writings of Peter Berg, edited by C. Glotfelty and E. Quesnel, pp. 41–51. Routledge, London and New York.

Berman, M. (1981) The Re-Enchantment of the World. Cornell University Press.

Daly, H.E. (1991) Steady-State Economics, 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Descartes, R. (1637) Discourse on Method, translated by Laurence J. Lafleur. The Liberal Arts Press, Indianapolis, USA (1950).

Devall, B. and G. Sessions (1985) Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered. Gibbs M. Smith, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT.

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2015) An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Beacon Press, Boston, MA.

Georgescu-Roegen, N. (1971) The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. Harvard University Press.

Greve, J.E. (2022) ‘Transformational’: could America’s new green bank be a climate gamechanger? The Guardian, 11 September 2022: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/sep/11/green-bank-clean-energy-climate-change.

Mazzucato, M. (2021) Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. Harper Business, New York.

McDonald, B. et al. (2019) The Amazon is still burning. Blame beef. The Dispatch, New York Times, October 6th 2019: https://www.nytimes.com/video/world/americas/100000006721982/amazon-rainforest-fires-burning.html?searchResultPosition=3.

Murison Smith, F.D. (2019) Economics of a Crowded Planet. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Murison Smith, F.D. (2020) A Planetary Economy. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Sackmann, I.-J., A.I. Boothroyd and K.E. Kraemer (1993) Our sun. III. Present and future. Astrophysical Journal, 418: 457–468.

Snyder, G. (1969) Four ‘changes’. In Environmental Handbook, edited by G. Debell, pp. 323–333. Ballantine, New York.

[1] From Indian Boyhood by Charles Eastman (1902), quoted by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the World (2014) p.136.

[2] Descartes (1637), quoted by Morris Berman in The Re-Enchantment of the World (1981) p. 25.

[3] Snyder (1969) quoted by Devall and Sessions in Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered (1985) pp. 171–172.

[4] Odum (1971, 1994).

[5] See in Steady State Economics, 2nd Edition, p. 203, by Herman Daly (Publisher, 1991).

[6] Georgescu-Roegen (1971).

[7] The average solar incidence upon Earth’s surface is about 6 kilowatts per square meter (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_irradiance). This equates to about 13.4 quintillion (13.4 x 1018) kilowatt-hours per year for the 255 trillion square meters (i.e., half) of Earth’s surface exposed to the sun at any given time. The world’s total energy consumption in 2017 was about 171 trillion (171 x 1012) kWh (www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/total-energy-consumption) or about 0.001 percent of total insolation. The sun will continue on its present main sequence for an estimated five to six billion years (Sackmann et al., 1993).

[8] Eric Beinhocker provides an engaging overview of the collective intelligence of the market as a complex system in his book The Origin of Wealth (2006).

[9] Mazzucato (2021).

[10] Globalists versus planetarians: an interview of Peter Berg by Michael Helm. In The Biosphere and the Bioregion: Essential writings of Peter Berg, edited by C. Glotfelty and E. Quesnel, pp. 41–51.

[11] ‘The Amazon is still burning. Blame beef.’ The Dispatch, New York Times, October 6th 2019, by Brent McDonald, Paula Moura, Ben Laffin and Emily Rhyne.

[12] ‘Transformational’: could America’s new green bank be a climate gamechanger? By Joan E Greve in The Guardian, 11 September 2022.

[13] Barnes (2021).

[14] It may seem odd for government to rent capacity to public enterprises because it looks like government renting capacity to itself, but actually national governments bill regional and local governments for all kinds of goods and services, as well as providing funding to them for diverse programs. It is perfectly normal for a governmental agency to bill itself for use of its own resources.

[15] Barnes (2014).